Wana leisure music is experiencing a period of great crisis; currently traditional music

is a matter for a few elders, who still own and use the few musical instruments in

circulation. The young are great music lovers but are much more interested in Indonesian

popular music. The passion for this music is so strong that they buy mobile phones just to

listen to MP3 recordings of it, there being no telecommunications signal in the jungle; the

phones are given to them by friends and relatives from outside the forest. Playing the guitar is very common among young people, and they mainly use the instrument to play pop hits.

I received many requests for new strings from my trips to Palu. It seems that music is maintaining its importance in Wana society, even though the traditional forms are being replaced by modern mainstream ones. Indeed, after centuries of vitality and presence in the community, Wana traditional music seems to be approaching the end of its time, and documenting and safeguarding this treasure has been a major motivation for me.

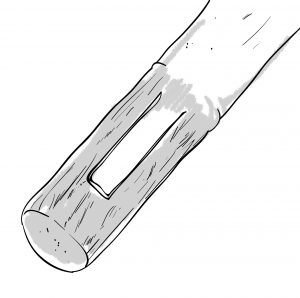

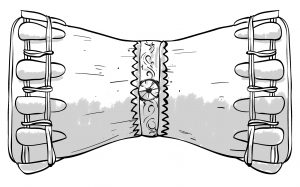

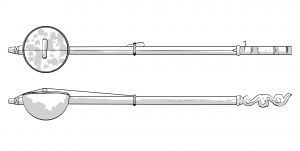

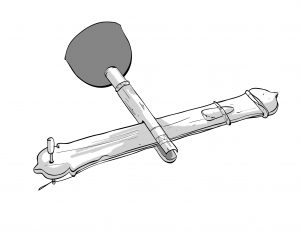

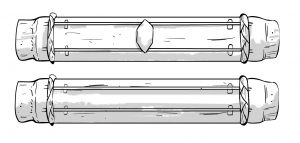

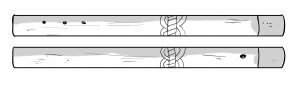

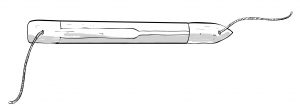

It has not been easy to approach this tradition. This is not because of a lack of Wana interest in sharing their music with me, but because of the difficulty in finding and reconstructing musical instruments and, ultimately, finding players. Often, people do not dedicate much care towards their instruments; they are, in fact, placed in the corners of their houses or between roof inlets and are often abandoned there for years. Usually, an unusable instrument is not replaced (again reflecting the idea of that which is not needed also not being wanted), effectively reducing the number of specimens and the possibility of their discovery by new generations. During my stay, I found with difficulty only two geso (spike fiddles), two popondo (chest resonators), and three tulali (flutes); for the other instruments, I had to find people able to make them. Even if traditional music is disappearing, the strong cultural connection between music and the invisible is still strong and crucial to understand Wana rituality and human-spirit relationships. As Friedson notes “music makes translucent the boundary between human and spirit” (1996: 100). As we will see, a few of these instruments have a direct connection with the invisible world, and they are able to affect material, emotional and spiritual realities with their sounds.

Wana people have a great awareness of the sound quality that an instrument must possess and the choice of materials is always aimed at achieving the best possible result. Even when forced by the lack of materials, for instance by building resonance boxes from plastic containers, the Wana always want to obtain the desired sound. They are also very careful and critical about the musical instruments built by other people; I encountered some that had been built by people considered not up to the task, and these people were widely criticised for sloppy work.

Many Wana people have great practical knowledge about music but do not possess a specific vocabulary; in fact, there are no words for “music” or “rhythm,” while they do clearly distinguish instrumental music (krambangan) from that for single voice or for voice and instrumental accompaniment (linga-linga). In addition, words do not distinguish clearly between the intensity and the pitch of a sound; the word malangan means both “high-pitched” and “strong/intense,” while the term rede is used to indicate a low-pitched and a low intensity sound. Each note is simply called soo (sound).